- Home

- Daniel Halper

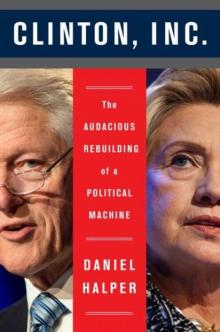

Clinton, Inc.: The Audacious Rebuilding of a Political Machine Page 12

Clinton, Inc.: The Audacious Rebuilding of a Political Machine Read online

Page 12

A former mainstream news correspondent tells me that the oft-cited reports of the Clintons screaming at each other and throwing lamps while living in the White House “really did happen.”

“He is cranky and yelling half the time,” says one former aide in our interview. “People don’t really talk about that, which is interesting, but he does.”

These aspects of his behavior seem to have created something of a distance between the former president and other people. Bill Clinton is largely a person for public consumption, not private. The charm works best on those who know him least.

His life is largely about politics, giving speeches that put him in the public spotlight and collecting chits for the future. “He’s done a lot of fund-raising, visiting, almost like the way the chair of the [Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee] would be going running around to races so much,” says a former Clinton press secretary.

Within the first few years of his postpresidential life, Clinton established the Clinton Global Initiative, a group that brought together private and public leaders to talk about ways to combat major problems, such as development in the Third World or poverty. CGI, as it was more commonly known, was started, according to a source, out of Bill Clinton’s frustration with the ponderous meetings of various global elites in Davos, Switzerland. He believed he could do the same thing with the Global Initiative, except more effectively.

Clinton used his celebrity to bring together people like Bill Gates, Warren Buffett, and the leaders of Rwanda at forums where he could charm them, flatter them, and have a bull session about whatever crossed his mind. The former president hosts events that gather CEOs and major hedge-fund investors. He is said to have been particularly successful at wooing Muhtar Kent, the CEO of the Coca-Cola Company, and Andrew Liveris of Dow Chemical. “He’s also developed an extraordinary network in the corporate and business community,” says a former Clinton official. Of course, that’s the right word. Network. Not friendships.

As some aides talk about their former boss, it’s hard not to see it as rather sad in its way. Just another way to try to satisfy an unfillable void in Bill Clinton’s life, with attention. “It’s a big event. A lot of people around,” says the former aide. “They talk about this, that, and the other thing. But there’s nothing to it, other than chatting.”

Contrary to the general impression of Clinton as the flawless charmer, his seemingly endless need for attention and approval, particularly from those who don’t like him, can sometimes backfire in dramatic fashion.

“These two old Jews are walking down the street.” The former president, always eager to please, was grinning as he retold a favorite joke to a group, which included some prominent Republicans, in 2003. Clinton was at the Turf Club at Baltimore’s Pimlico Race Course on Preakness Day with Doug Band, Jon Bon Jovi, Maryland governor Robert Ehrlich, other well-heeled celebrities, and his host for the day, Frank Stronach, an auto parts billionaire.13

Clinton, who couldn’t resist knowing everything about everything, offered reporters his prediction for the race—the New York–bred Funny Cide. He made the choice, he said, “In deference to the junior senator from New York.”

As he made his way to a table of Republicans, which included Tucker Carlson and his father, former U.S. ambassador Richard Carlson, Clinton could not help trying to ingratiate himself. How to do it? Well, his audience being Republicans, Clinton apparently assumed that anti-Semitic jokes were totally appropriate and welcome.

As the joke begins, everyone around the table looks dubious. Where is he going with this? Surely the former president of the United States is not about to tell an anti-Semitic story in front of people he hardly knows. This, of course, is exactly what he does, according to a number of the people present.

Clinton’s story about “two old Jews” takes them to a Catholic church, where they encounter a big sign reading, “Be a Catholic. We’ll pay you a hundred bucks.” One of the Jews, whom Clinton names Abe, says, “Well, that sounds like a pretty good deal. For a hundred bucks I’ll do anything.” He tells his friend to wait outside. If he does, the friend gets half of the money.

Clinton describes Abe going into the church, meeting with priests, and learning the traditions of the Church. “Son, you’re now a Catholic,” the priest tells him.

Abe collects the hundred dollars and walks back outside, where his friend is waiting. “Hey! Look at the new Catholic here,” the friend declares. “You got my money?”

Abe shakes his head. “You fucking Jews,” he says. “It’s all about the money, isn’t it?”

As the former president laughs, the others offer weak smiles. No one wants to offend him. So Clinton goes on to tell a complicated anti-gay joke, involving a hermit living in a cabin in Arkansas. “The joke was really weird,” says one of the attendees, who couldn’t recall the details with any specificity. The former president has long seemed visibly uncomfortable about gays, according to acquaintances. Once the president spotted a male acquaintance and complimented him facetiously about wearing a pink tie. The acquaintance replied, “Thank you, Mr. President, I wore it just for you.” Clinton was silent for a long moment. He looked frazzled, then furious. The gay-tinged repartee “made Clinton nervous,” a participant in the conversation recalls.

Doug Band was no better at making strangers feel comfortable that afternoon at the racetrack. “You know there’s this model,” he said. “The press is saying Clinton’s fucking her.” He looked offended. “I’m the one who’s fucking her.” (The model Band was bragging about was Naomi Campbell, whom the Washington Post would tie the aide to a few years later.)

As Band holds forth, Clinton walks back to the table with another awkward recollection.

“You’ll remember I had that trouble with Gennifer Flowers,” Clinton tells the stunned guests. Of course, they all remember. “The day the scandal broke, we were having a meeting and James Carville came running in and told us that Gennifer Flowers is holding a news conference, right now to say all these things about me.”

Clinton continued, “Carville comes in. He says, ‘She’s saying all these bad things, all these terrible things about you. And claiming that she had an affair with you and so forth.’ ” The tableful of people listening to Clinton had no idea where he was going with the story. “Well, Stephanopoulos fell on the ground,” said Clinton, referring to his former aide and now ABC News personality George Stephanopoulos. “George fell on the floor. And he curled into the fetal position and he started crying. ‘It’s over. It’s over. We’re done, you know. You’re going to destroy us and all that.’ So Carville kicked him.”

As the guests looked on amazed, Clinton lapsed into a pretty good imitation of Carville’s well-known Cajun drawl. “Carville said, ‘Get up, bastard, stop doing that. What’s the matter with you, you stupid motherfucker?’ ”

In Clinton’s version of the story, Stephanopoulos then gets up. “And he’s sniffling and he’s all upset,” Clinton told the group. “And Carville says, ‘We’ll weather this, we’ll take this on, we’ll do whatever.’ ”

Clinton finished the story with a smile. The group of strangers was stunned that Clinton would go out of his way to trash his former aide in such a manner. Some, however, had their theories for his motivation—that Clinton was still feeling vengeful over the memoir Stephanopoulos wrote about his tenure with the Clintons.

“He laid George Stephanopoulos out,” one participant recalls. “It made him look like a little girl. Clinton used that phrase, saying he was even crying like a little girl.”

The recklessness of Clinton’s jokes and comments was perhaps rivaled by his behavior that day. At least two participants at the event confirmed a story involving Clinton and a woman often linked to him in newspapers and magazines over the years—Canadian politician Belinda Stronach, the daughter of Clinton’s host that afternoon, Frank Stronach.

In June 2003, the Vancouver Sun reported that “Stronach, [then] 36, and Clinton, [then] 57, have been spotte

d together on at least three other occasions, including a private dinner last July when he was in Toronto to honour rock and roll legend Ronnie Hawkins. Over the past six months, the two have dined together at the Democratic governors’ conference in Baltimore as well as a Democratic fund raiser in California.” The newspaper noted that spokesmen for both Clinton and Stronach insisted the relationship was not romantic.14

In 2008, as Hillary made a bid for the White House, Vanity Fair also alluded to Clinton’s questionable relationships with women, naming specifically the actress Gina Gershon and Stronach. The propriety of the Clinton-Stronach relationship was also alluded to in the New York Times in 2006 under the headline “For Clintons, Delicate Dance of Married and Public Lives,” which stopped short of accusing the former president of adultery. “Several prominent New York Democrats, in interviews, volunteered that they became concerned last year over a tabloid photograph showing Mr. Clinton leaving B.L.T. Steak in Midtown Manhattan late one night after dining with a group that included Belinda Stronach, a Canadian politician,” the Times reported.15

Clinton insiders date their first meeting to 2002, when Stronach was married to a Norwegian speed skater named Johann Olav Koss. With rumors of the Clinton-Stronach relationship already making the rounds in elite social circles, what Clinton did next, in the view of witnesses, seemed ill-considered at best. According to former ambassador Carlson, Clinton drove off with Stronach, described as an attractive woman wearing a tight, short skirt and displaying what an attendee called “a ton of cleavage.”

Belinda didn’t bother to tell her father that she was leaving with Clinton, and according to Carlson, “her father was freaked out. He was running around, upset she wasn’t there.”

The two returned just before the first race.

Such behavior was anything but charming. Indeed, it demonstrated, as the Times warned, Clinton’s penchant for interfering with his wife’s political ambitions: “Just as it is difficult to predict how voters would feel about Mrs. Clinton as a presidential candidate, Clinton advisors say, it is hard to foresee how they would judge the Clintons’ baggage in the context of their third White House bid.”16

“Mr. Clinton is rarely without company in public,” the Times went on to note, “yet the company he keeps rarely includes his wife.”17 At around that same time, ironically enough, Hillary Clinton was on the Senate floor defending the institution of marriage during debates over gay marriage legislation.

“I believe that marriage is not just a bond but a sacred bond between a man and a woman. I have had occasion in my life to defend marriage, to stand up for marriage, to believe in the hard work and challenge of marriage,” Hillary said on the floor of the Senate on July 13, 2004, discussing a constitutional amendment regarding marriage and her support for the Defense of Marriage Act.

“So I take umbrage at anyone who might suggest that those of us who worry about amending the Constitution are less committed to the sanctity of marriage.”

As the 2004 election dawned, Bill Clinton was still making every effort to ingratiate himself with Republicans, so much so that he had taken to comparing his administration to that of the business-friendly Dwight D. Eisenhower. Many liberal Democrats bought that argument, too, and the backlash gave rise to a progressive movement that saw a primary reason for existence in countering the Clintons’ studied moderation and chumminess with big business and Wall Street.

Running as a candidate of the left, Vermont governor Howard Dean criticized the Clintons, though in veiled terms, as “the Republican wing of the Democratic party.”18 The attacks were said to have infuriated Bill Clinton, newspapers reported at the time. Though Dean did not win the Democratic nomination that year, his liberal supporters yearned for another candidate to challenge what increasingly came to be seen as the Clinton Democratic establishment.

Still suffering from middling approval ratings, Hillary took a pass on the 2004 race against the incumbent Bush. In truth, it wasn’t her move entirely. Clinton pleaded with John Kerry to select Hillary Clinton as his running mate. But he was rebuffed.

“I think she looked at it,” a former Clinton aide tells me in an interview, “and saw that it wasn’t a really good shot. They saw that they didn’t really want to take on an incumbent, you know. Because taking on an incumbent is harder.”

The deciding vote appeared to have come from Chelsea Clinton. According to published reports, the former first daughter urged her mother to keep her promise to New York State voters that she would serve a full Senate term if they elected her. At that point, Hillary, if she was seriously entertaining it at all, firmly closed the door on a run.19

Besides, Bill was already working on an important side project in the Clintons’ charm offensive—one that promised to offer heavy dividends. He sought to make the Bush family, perhaps his most notorious political enemies, his new allies. And he succeeded in a historic fashion, changing the Clintons’ political fortunes dramatically.

4

Seducing the Bushes

“For their own reasons, the Bush people thought having Clinton with his father would be clever. They’re right. The consequence may be a Hillary Clinton presidency.”

—Newt Gingrich

If Clinton hoped to rehabilitate his image, and by implication Hillary’s, an improbable bonhomie with his most well-known adversaries would be an excellent beginning.

Just before 1 a.m. on December 26, 2004, tsunamis six stories tall crashed into the coasts of Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Thailand, and about a dozen other nations. The tsunamis’ cause was an oceanic earthquake registering magnitude 9.0, and its effect was massive devastation and death. More than two hundred thousand people died, and millions more were left homeless. Survivors needed medical care in the short term and an almost unimaginably costly rebuilding effort in the long term. In between, something needed to be done to stave off famine and the spread of disease.

Governments and private citizens across the globe were quick to promise tremendous amounts of aid—including a pledge of $350 million from the United States. But how to channel it all? How to minimize waste and make sure the money found its way to the people who could do the most good? And, since it would take about $10 billion to rebuild what the tsunamis had destroyed, how to raise enough?

The answer, President George W. Bush decided, was to put his father and his predecessor in charge. They had the gravitas. They excelled at fund-raising. And neither would be distracted by a day job. Both men immediately agreed to W.’s request to head the relief mission, and in February 2005 they spent four days in Thailand, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and the Maldives—an island nation that had lost 62 percent of its gross domestic product. Clinton saw in the trip an opportunity to help not just the wrecked region, but his family’s political fortunes as well.

“Being next to Herbert Walker Bush was good for Clinton,” says John McCain, who has observed both men up close for decades. “Bush 41 always had an unimpeachable reputation. I mean service in World War II; you know all the things that he did.” Clinton could only benefit from the proximity.

The psychology of the elder Bush is not complicated. Despite his later efforts to model himself a Texan, the elder Bush grew up an aristocratic Connecticut Yankee, in a land of country clubs, prep schools, and noblesse oblige. Bush’s maternal grandfather founded golf’s Walker Cup, and his father, Prescott, was a United States senator. Their country-club set prizes graciousness, good manners, and kind gestures, even small ones.

The old man “is the last of the great gentlemen,” an admiring former aide to the senior Bush tells me.

“We all love Bush 41,” John McCain says fondly. “He and Gerald Ford, both losers, were viewed in my life as two of the nicest people that inhabited the White House.”

Trained by his mother to demonstrate modesty and embrace service, Bush the elder is susceptible to graciousness as well as flattery. Greenwich, Connecticut, was a world where such messy things as ideologies were nuisances. A place where big ideas were

dwarfed by small kindnesses and the proper showing of deference.

Bill Clinton’s wooing of the senior Bush thus began with the friendliest of arguments. As the former opponents flew together on an Air Force Boeing 757 toward South Asia, they argued over which ex-president would get to sleep in the lone bed. Bush, whose patrician politeness was the closest thing he had to an ideology, insisted Clinton should take it. Clinton wouldn’t hear of it. Touched by this act of selflessness, Bush would later say, “That meant a lot to me.”1

In truth, it wasn’t that big of a sacrifice. As an aide later told me, Clinton ended up playing cards all night with Bush’s chief of staff.

Clinton’s “good son” act continued at every stop, when Clinton would respectfully wait at the bottom of the plane’s steps while the octogenarian Bush slowly descended. Clinton knew and at every opportunity abided by the code of chivalry Bush followed—the unwritten rules of small gestures, tactful words, and signs of respect passed down from Prescott Bush and his wife, Dorothy Walker Bush, to the heirs of their dynasty.

The senior Bush was smitten. As he would later gush to presidential chronicler Hugh Sidey, “I thought I knew him; but until this trip I did not really know him. . . . He has been very considerate of me.”2

To be sure, on the tsunami trip Clinton wasn’t always on his best behavior. He talked too much for Bush’s tastes, and he was always running late—a true taboo in BushWorld. He also hit on Lani Miller, the redheaded White House aide whom Clinton couldn’t resist telling, “You remind me of my first girlfriend.” It was interpreted as a pickup line, not a literal comparison. Before Bill Clinton’s trip to South Asia with George H. W. Bush, he was held in unreserved contempt by many—perhaps most—Republicans, but after the trip and the many pictures and footage of the two former enemies hand in hand amid carnage and disaster, Clinton’s approval rating climbed.

Clinton, Inc.: The Audacious Rebuilding of a Political Machine

Clinton, Inc.: The Audacious Rebuilding of a Political Machine