- Home

- Daniel Halper

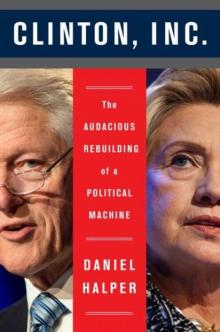

Clinton, Inc.: The Audacious Rebuilding of a Political Machine Page 5

Clinton, Inc.: The Audacious Rebuilding of a Political Machine Read online

Page 5

Indeed, once Giuliani dropped out of the Senate race and Lazio announced a Senate bid, the Clinton team went after him with ruthlessness and relish. “They were the first to go negative and went negative hard,” Lazio recalls, and the president was quick to use his position to help Mrs. Clinton make her moves. President Clinton held up legislation until after the election and made the White House photography office an arm of the Hillary Senate campaign.

“I had gone over to Israel as part of a congressional delegation—two House members, two Senate members, and the president, and Hillary. One of the lunches that we were at was with Yasser Arafat and the Palestinian Authority,” Lazio recalls. Hillary “at the time was totally effusive with Arafat and his wife, [but] an official White House photographer had gotten a picture of, on the reception line, of me shaking the hand of Yasser Arafat and smiling. Her campaign got that, got access to that, and used that . . . certainly the media never called her out on that.”

To the contrary, the media, in Lazio’s retelling, played right along, making it an issue that Lazio had been photographed with a top terrorist and enemy of the Jewish state. In all, it was an “absolutely ruthless campaign operation,” remembers Lazio.

Leading the charge for Hillary was her communications director, Howard Wolfson. Many Democrats have questioned his loyalty to their president, their party, and their principles—Wolfson would later go on to serve as chief spokesman for Republican-turned-independent New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg—but no one on either side of the aisle has ever questioned his loyalty to Hillary Clinton. An intense, neurotic, and foul-mouthed workaholic, Wolfson was a natural commander of the rapid-response Clinton campaign operation. His cutthroat operatives ran opposition research, fought back against criticisms, and tracked almost every word written or spoken about the campaign, searching for opportunities to exploit. Wolfson was the living, breathing embodiment of the Untouchables-inspired line he told his team: “If he uses a fist, you use a bat. If he uses a knife, you use a gun.”24

Wolfson is loud and aggressive at work, but can be quiet and extremely shy in social settings. He’s part of the establishment, but loves indie rock (and writes about it frequently). He’s polished and professional in his rhetoric, but Spartan in his dress and personal tastes. Throughout the 2000 Senate campaign, Wolfson’s living room had a single piece of furniture (a couch); his bedroom had only a bed; and his television sat on the cardboard box it came in. When Clinton’s Secret Service detail gave him identification pins, the agent said, “I’m giving you two—one for each of your suits.”25

The ferocity of the attack on Lazio was necessary. Hillary Clinton was not going over as well with New Yorkers as she had hoped. In an eerie precursor of her 2008 primary campaign, she was statistically tied in the polls with a legislator who was relatively unknown outside his congressional district.

Hillary Clinton might well have lost that Senate race—and dashed her presidential hopes—had she not gotten a bit of good luck and an assist from the media. A turning point came during a highly anticipated television debate with moderator Tim Russert, the respected NBC News bureau chief, former Moynihan aide, and host of Meet the Press.

During Clinton’s debate preparations, her dear friend Bob Barnett, the Washington lawyer and book agent, portrayed Lazio. But nothing in those practice sessions had prepared Hillary for the shock of being onstage with a baby-faced, little-known congressman who considered himself her equal. “She had a completely offended look on her face,” recalls Lazio. “I didn’t believe it because of my particular point of view. I think it was the mere idea that it was the first time anybody had really publicly challenged her.”

Russert, too, turned out to be an aggressive questioner of Clinton, which the Democrat did not appreciate.

“Hillary appeared offended at times that she was being challenged,” says her opponent. “When I pressed her and challenged her on different things, different policy issues, she looked at me like how dare you even question me on these things.”

It was in that debate, where Hillary, wearing a classic teal pantsuit, met the telegenic Lazio, who was amped up for a fight. She had never herself debated in an election setting. And here she was, being challenged on taking allegedly dirty campaign money and being asked to sign a pledge not to take so-called soft money.

Looking for a dramatic flourish, Lazio reached into a breast pocket inside his suit jacket and pulled out a pledge against soft money in the race. “Well, why don’t you just sign it?” Lazio said, challenging Hillary. She stammered.

“I’m not asking you to admire it; I’m asking you to sign it.” Lazio could see he was successfully putting her in an uncomfortable position. And her next words would give him, he thought, an opening.

“Well, I would be happy to—when you give me the signed—”

The camera panned out from its close shot of Hillary and caught Lazio darting from his podium toward hers.

“Well, right here,” he said, sticking out a bundle of papers. “Right here. Right here, sign it right now.” He was physically putting the pledge on her podium—and in the process coming inches from her.

Hillary looked immediately flustered and turned to her opponent, who was at this point mere inches from her. “We’ll shake on this,” she said, sticking out her right hand.

“No, no,” Lazio said, instinctively shaking her held-out hand, but then quickly pulling his hand away from hers. “I want your signature.” He used his just-released hand to start pointing at the documents. “Because I think everybody wants to see you signing something you said you were for. I’m for it. I haven’t done it. You’ve been violating it.”

His finger was no longer pointing at the papers. It was pointing directly at her. “Why don’t you do something important for America. While America is looking at New York, why don’t you show some leadership because it goes to trust and character.” Lazio turned his back toward her as he finally returned to his podium.

Lazio finished the debate thinking he had won. He went to the spin room to say so. Hillary was nowhere to be found. “It was very interesting. When that debate ended, Hillary stormed out of there. She did not take the traditional questions from the press afterwards in the spin room.” It was, according to Lazio, a sign that Hillary, too, believed he had won this round.

But within hours, what Lazio thought was a victory quickly turned into a defeat. Hillary Clinton did what she would often do when it worked to her political advantage—she played the gender card. The Clinton campaign latched on to the moment Lazio stepped into Hillary’s space as threatening, invasive, and sexist.

“They had gotten the clip out” in nearly no time, Lazio says, and were “suggesting it was misogynistic to challenge Hillary on the debate set.” Lazio laments, “We completely got mauled in the media by the Clinton machine, who just drove this message relentlessly, again at a very supportive media.”

It was Hillary’s first debate—and a sign of what would come. It was possible to defy reality, the Hillary campaign learned. It was possible to take a debate loss and turn it into a win. It just took a single moment to seize and that could eclipse everything else. And it took some friends in the press to push that narrative. Which they did. Before long, polls put Hillary into the lead.

Once she got the hang of New York, she was a meticulous campaigner. One former Secret Service officer on her detail remembers driving her around and learning very quickly that Mrs. Clinton is a backseat driver. “She’s a bit of a micromanager. She’d always kind of tell us . . . thought she knew New York really well and didn’t know the streets, I think, as well as we did.”

They were driving around New York in an armored brown van, “which we had called the mystery machine, the Scooby Doo van, which was an interesting thing to drive and learn to manipulate,” the agent tells me in an interview. That’s because Hillary and her staff objected to the customary limo the First Lady would normally use. They complained the “optics” weren’t right for an aspiri

ng senator who wanted to look like she was a woman of the people—and not a product of the White House.

Her celebrity helped her. Not many first-time candidates for Senate have their own military jet and Secret Service detail, an immediate attention grabber wherever she might go. Lazio contends that her presence alone—and one must credit her: she showed up in the smallest New York towns—helped turn what otherwise might be right-of-center voters toward her side. “When she pulls into town with this media entourage and with the Secret Service entourage and she’s the sitting First Lady of the United States and she’s coming to the Chamber of Commerce event with fifty people or one hundred people, the usual audience, they’re starstruck,” he says.

Hillary won the election handily. She’d get 55 percent of the vote, while Lazio got only 43 percent. She’d get the support of nearly 3.75 million voters, while Lazio would get close to a million votes fewer—2.9 million. Interestingly, at the end of the day, Hillary Clinton lagged behind Al Gore’s margin of victory over George W. Bush in New York—a sign perhaps of timid but not overwhelming support in the heavily blue state.

“She grinds it out,” Republican strategist Mike Murphy, who worked for Lazio during that election, recalls in an interview. “She was very tough and just relentless. She just keeps going. That’s how they do it. That’s what the old pros do who won and lost before. She’s been through winning and losing in Arkansas with him and that’s a useful skill to have, ring-wise. But there’s no flash of inspiration or genius; she just ground it out and the Democrat won the Democratic state.”

The victory thrilled some New York Democrats, but not all of them.

Her victory party that night at the Grand Hyatt Hotel on Forty-Second Street in Manhattan demonstrated the less than comfortable relationship she had with many Democrats, most of them weary of a decade of defending the Clintons and worried about what new trouble they’d find themselves in now.

Reporters present at the event recalled a rather perfunctory affair, though Moynihan, for one, seemed to acquit himself with grace of the chore of handing over his seat to a person he thought an unworthy carpetbagger. As did other prominent Democrats who privately looked askance at the audacity of the run—the New York branch of the Kennedys among them. Officially, so did her would-be colleague, Chuck Schumer.

What has never been revealed, until now, is the subversive role the would-be senior senator from New York—Chuck Schumer—was playing from the outset of Hillary’s pursuit of public office. The Clinton-Schumer tension had been the subject of rumors and speculation for years. “Chuck Schumer hatched secret plan to get Obama to run,” a New York Post headline blared in 2010.26 A book at the time described the senator’s efforts to “betray” his colleague by recruiting Obama for the White House. “Schumer and the others were concerned about Clinton’s political vulnerabilities,” the book argued, according to the Post.27

But what was not well known is that the tensions between the two went back even further than the 2008 race. Schumer had served with Lazio in the House of Representatives and, as members of the same state delegation, they knew each other well. Schumer took an unexpected interest in Lazio’s Senate campaign from the outset, finding opportunities to chat with the Republican on shuttle flights to Washington or when they encountered each other on the grounds of the U.S. Capitol. Schumer would offer Lazio unsolicited advice.

“I thought he was generally . . . he was supportive,” Lazio recalls. “Quite helpful to me behind the scenes and encouraging. I just would say that it was clear to me anyway that he would not have been disappointed if I had been elected.”

Pressed as to whether Schumer actually devised lines of attack against Clinton, Lazio demurs. “I don’t really want to get into that or answer that question,” he says. “I think I would just say he was generally supportive and, in my informal discussions, encouraging.”

The revelation of Schumer’s role makes sense to longtime Democratic strategist Bob Shrum. “Look, if you were the other senator from New York and she was in the Senate, you just sort of have to resign yourself to the fact that, you know, you might be called the senior senator, but in a way you weren’t,” he says.

What is more puzzling is that Schumer’s offensive against Clinton continued even after she was elected. He was known to leak damaging information about his Senate colleague to the Rupert Murdoch–owned New York Post. Most likely this was done as much to ingratiate himself to the influential tabloid as it was to undermine Hillary. But the continued Schumer-Clinton rivalry underscored an interesting aspect of Hillary Clinton’s Senate career—and potential second run for the White House. Like her husband in his postpresidential life, she tended to have more of a knack for building bridges with her enemies than she did with her friends.

Soon after Hillary Clinton beat Rick Lazio to win the Senate seat in 2000, Lazio remembers finding himself in the Oval Office with her husband, President Bill Clinton. The president was then a lame duck—he was finishing his tumultuous second term and getting ready to transition from being the commander in chief to life as a political spouse, now that his wife was going to be the junior senator from New York and he was going to be an officially unemployed husband in a foreign state.

The meeting wasn’t awkward, though, as one might expect when the political loser comes face to face with the spouse of his opponent who just beat him. It was quite the opposite: friendly and fun. They were sharing jokes.

Lazio was there because the president, finally, was going to sign a couple of bills that he had held until after Lazio’s election against his wife. Lazio thought the timing was suspicious. “They wanted to deny me that photo-op,” Lazio remembers thinking, over a decade later in an interview, until after the election.

One of the bills he remembers being in there to speak about was regarding breast cancer treatment or perhaps it was the environmental bill they were to celebrate.

Either way, Lazio thinks, Clinton had performed his duty as husband—by denying Lazio the image of being the moderate Republican able to work with the Democratic president. And now that that duty had expired, Clinton was performing the next duty: signing the bills that Congress passed into law.

But then something dramatic happened to change the mood. “Unexpectedly she came in to the Oval Office,” Lazio tells me with a little laugh. “He [Bill Clinton] froze like a deer in the headlights and backed away from me as if I was uranium.”

Winning a Senate seat meant Hillary needed a place to live in Washington, since the Clintons would be moving out of the White House. She settled on a 5,152-square-foot brick structure on Whitehaven Street, just around the corner from the vice president’s residence at the U.S. Naval Observatory in Northwest Washington, D.C. It was in this house that Hillary Clinton would later film her 2007 video announcing her bid for the 2008 Democratic nomination.

With three stories, attractive black shutters, four bedrooms, and seven bathrooms, the home cost the Clintons $2.85 million in 2001—considerably less than the asking price of $3.5 million. The District of Columbia now assesses its value at around $4.5 million, which puts the Clintons’ annual property tax bill close to $40,000, about the same as the salary of the average American. (In 2012, the Clintons got slapped with a $1,883.75 penalty for paying taxes on the home late, according to real estate records, and had to pay an additional $445.04 in interest on the late payment.)

When the time came to renovate Hillary’s new home, her interior decorator, Rosemarie Howe, expected the senator to be too busy to care about a lot of decorating details. Clinton wasn’t. Referring to an interview with Howe, the Washington Post reported in 2007 that “the senator from New York has been very involved in updating the Whitehaven Street property, which they’re swatching through room by room. Howe has finished the living room, dining room and kitchen, yet is always searching for special pieces and fabrics to update the look. Upstairs, she has redecorated the bedrooms, including Chelsea’s digs when she’s in town. Downstairs, she has added storage

to the basement.”28

Howe says Hillary “makes decisions quickly but does it with enjoyment”—perhaps because the decisions are far easier and much less important than the political, personal, and public-policy choices she would have to make in her eight years as senator.29

While Hillary was preparing to enter the Senate, Bill was closing out his time at the White House—and scandal continued to dog him and tarnish his wife’s own efforts. At the center of the latest controversy was Clinton’s never-ending quest for money and the potential compromises he was willing to make to get it.

Toward the end of the Clinton administration, the president sought to close out business and prepare for life beyond the walls of the White House. So did the many, many political appointees, from across government agencies, whose work would come to an end when George Walker Bush was sworn in and the Democrats handed over power to their Republican counterparts.

One of those bureaucrats seeking another line of work was Louis Freeh, the former director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Had it been up to Bill Clinton, Freeh would’ve been out of work years earlier. He was a constant thorn in the side of the president. It had been Freeh’s job to keep appropriate distance from the person who was both effectively his boss and who was at the center of a series of investigations that were faithfully carried out by the FBI. And since he was investigating the president, it wasn’t as though Clinton could fire Freeh; it in fact heightened his job security in a way not comparable to any other government bureaucrat.

As FBI director, Freeh had had the unprecedented task of taking a DNA sample from the president of the United States so that it could be compared to the DNA in the semen stain on Lewinsky’s infamous blue Gap dress. The exchange took place in secret—the president was at an official event when he pretended to have official business in the other room and slipped out momentarily to provide his sample to awaiting FBI agents. That Bill Clinton suffered such an indignity in front of a man who despised him only furthered the level of enmity between the two.

Clinton, Inc.: The Audacious Rebuilding of a Political Machine

Clinton, Inc.: The Audacious Rebuilding of a Political Machine